UK RE-RELEASE REVIEW: NAPOLÉON

The Film: ★★★★ The Score: ★★★★

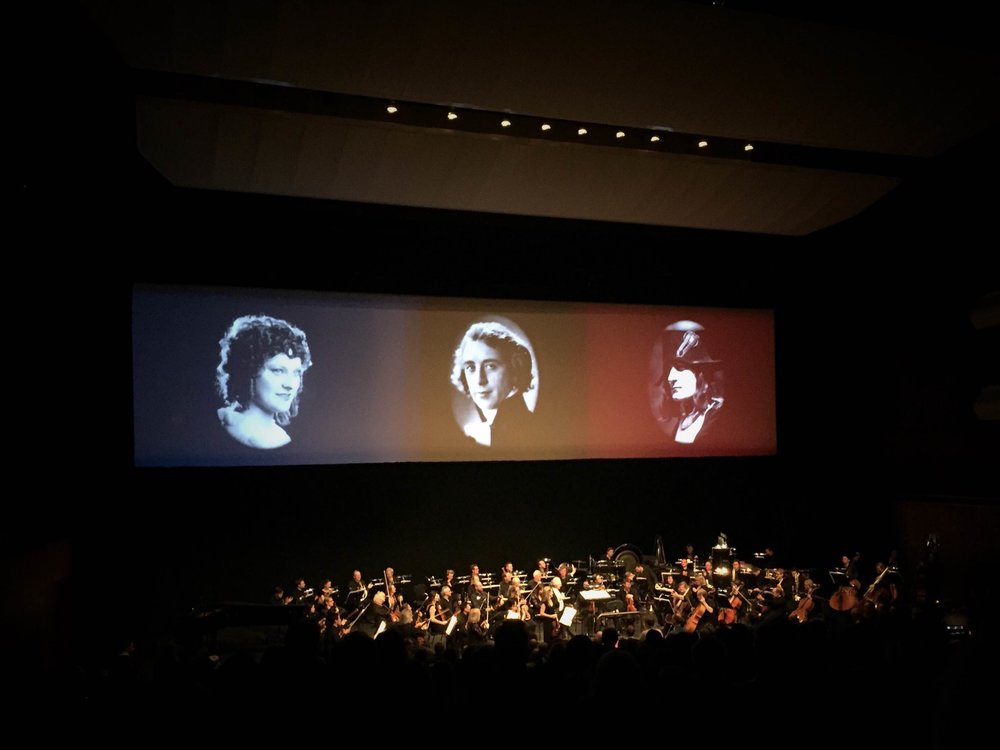

On 11th November 2016 the British Film Institute will release a new digital restoration of Abel Gance’s stupendous portrayal of the early years in the life of Napoléon Bonaparte. Ahead of the official release, I was fortunate enough to attend the first of several concerts at London’s Royal Festival Hall in which the film was presented with a live performance of Carl Davis’ score – a moving and thrilling cinematic experience that simultaneously transported its audience through time to the French Revolution and to the heyday of silent cinema.

View fullsize

Napoléon Bonaparte makes a heroic escape with the tricolour as his sail.

Napoléon (a.k.a. Napoléon vu par Abel Gance, 1927, France – restoration: 2000/2016, France/UK) written, produced & directed by Abel Gance / starring Albert Dieudonné, Gina Manès, Nicolas Koline, Edmond van Daële, Alexandre Koubitsky, Antonin Artaud / cinematography by Jule Kruger & Joseph-Louis Mundviller / restoration: edited by Kevin Brownlow / music by Carl Davis

Clocking in at no less than five and a half hours, British editor Kevin Brownlow’s restoration of Napoléon is the most complete version of this epic biopic to date. What is so special in 2016 is that the British Film Institute is now releasing the digital restoration of Brownlow’s reconstructed cut in cinemas, on DVD, on Blu-Ray and online. In so doing the BFI finally makes this daring, spectacular poem of silent cinematic language available to the masses, whereas it only previously existed on a handful of 35mm prints. The release of this digital restoration was given an appropriately grand gala at London’s Royal Festival Hall on 6th November, where Carl Davis conducted the Philharmonia Orchestra in a live performance of his score for this near-definitive version of a film so huge that it belittles even D.W. Griffith’s magnum opus, Intolerance (1916).

A single image commanded me to see Abel Gance’s silent epic. The trailer for the 2016 re-release features an outstanding wide shot of a cloaked rider and his steed galloping across a hilltop, silhouetted against the shimmering, moonlit sea. Such a grand, dynamic image grabbed me in the same way as the image of a land speeder trundling past a crashed star destroyer in the trailer for Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015) did. It is the sort of image with which the filmmakers (and editor of the trailer) make a promise to the audience: this film is going to be MASSIVE. The action sequence in which the moonlit image features is one of many crown the jewels in a film the roars with outstanding action filmmaking and technical innovation – from mounting the camera of the back of a horse, to expressionistic montage on a triptych of three screens at the film’s finale! Projected on the big screen with the full power of Davis and his orchestra underneath yielded one of the most memorable cinematic experiences I have ever had.

Planned as the first of six films charting Bonaparte’s life, Napoléon was the third (but by no means the longest) film by Parisian writer-director Abel Gance, which was made with the support of Charlés Pathé and released to great critical acclaim (and no small amount of political controversy) in France in 1927. Notably, this was the same year that Al Jolson’s The Jazz Singer electrified the film industry with the introduction of sync sound. Though the silent era birthed many more of its greatest works over the coming years, such as Metropolis (1927), Sunrise (1927), La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), Man With a Movie Camera (1929) and City Lights (1931), it became clear that sound was the future of cinema. Even if the talkies had arrived much later, it is unlikely that Abel Gance would have had the opportunity to realise his complete vision: a definitive history of the life of Napoléon Bonaparte on film. The costs incurred by the massive scale of Gance’s production, from its technical innovations to the many thousands of extras needed for its breath-taking sequences depicting the French Revolution and Napoléon’s invasion of Italy, were too great, too unwieldy to make further entries in the series possible. The un-commercially long run time of the film did not help matters, and Napoléon was a flop abroad, where the mangled two-hours cuts released by British and American distributors were largely savaged by critics. What a shame it is that this should have been the fate of Gance’s vision. One can only imagine the heights that future instalments might have reached, had Gance been able to build upon the technical innovations and grand spectacle laid out in this entertaining, patriotic, if uneven first chapter.

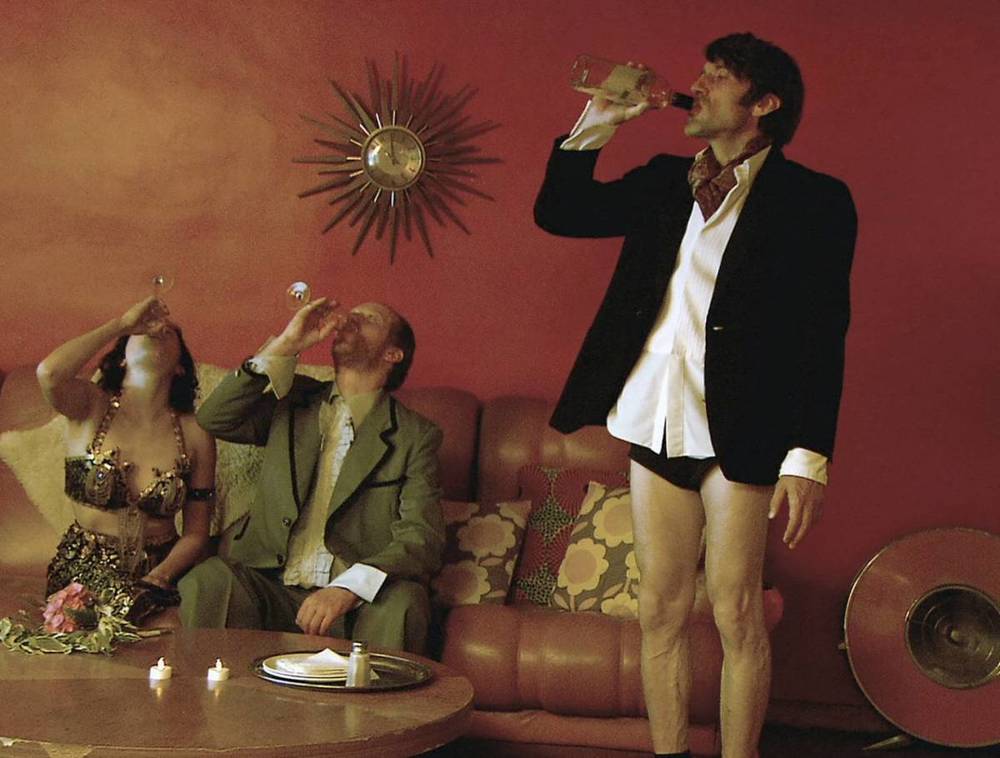

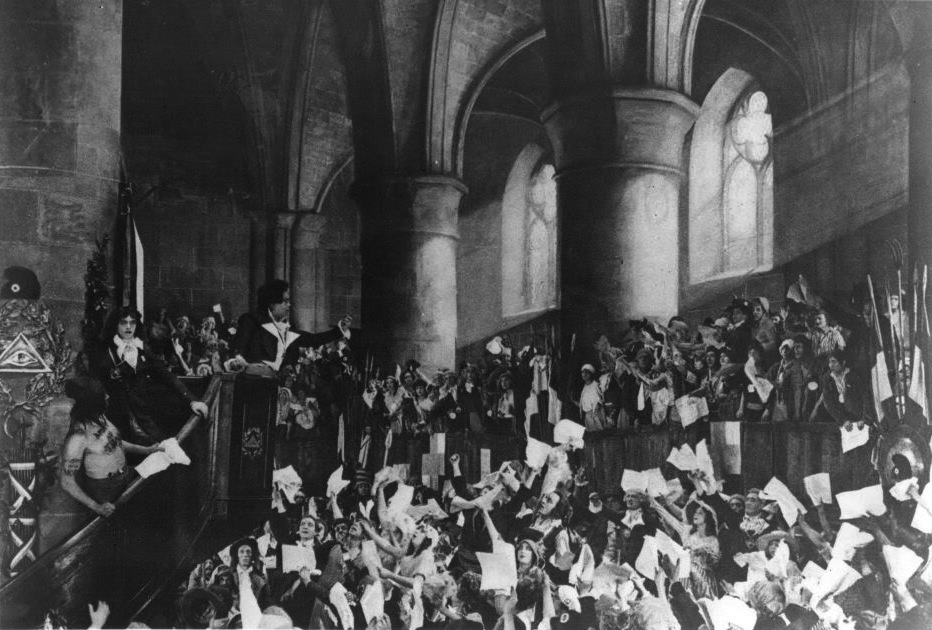

View fullsize

The unwashed masses of the French Revolution sing Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle’s anthem, ‘La Marseillaise.’

Approaching a far more focussed timeframe than its 330-minute run time would suggest, Napoléon covers Bonaparte’s life from his adolescence as a cadet at the military academy in Brienne, up to his appointment as the commander of the French forces invading Italy to oust the Austrians in 1796. The story that follows Napoléon’s proud and fiery resistance of the boys that bully him at Brienne College takes him from the bloody streets of Paris during the French Revolution; to a thrilling escape from traitors in his native Corsica; to his first victory against the British on the muddy battlefield of Toulon; to his imprisonment during the Reign of Terror; to his marriage to Joséphine de Beauharnais; to his successful defeat of the Royalist uprising; and eventually to his march over the Alps, into Italy, with the tricolour waving at the head of a column of soldiers and the eagle of destiny soaring overhead.

Albert Dieudonné’s virtues as a performer in the role of Napoléon are the same as those virtues that Dieudonné and his director decided Napoléon should impress upon the other characters. Dieudonné’s affectation of the stern, heavy body language with which this “stump of a man” dominates his opponents is both comical and genuinely convincing as a commanding presence. Dieudonné manages to nail the hard stare that neuters the over-inflated egos of arrogant generals and effects people in much the same way as Jesus Christ’s gaze on the Roman soldier in Ben Hur (1959). But the filmmakers are not ignorant of the silliness inherent in such a relentlessly serious character and they permit some fun at the expense of their hero’s preternatural authority. It is worth mentioning that Abel Gance and his cast take every opportunity to make Napoléon funny. From cute insert shots, such as a kitten hiding in the barrel of a rusty cannon, to dry banter, to the gallows humour of a seven-year-old drummer boy at the battle of Toulon cheerfully proclaiming that he must have at least six years left to live if the famous drummer boy, Viala, was thirteen when he was killed. Gance habitually disarms the audience and cuts his huge historic figures down to size with comic flourishes. Though largely humourless, and suffering from the same bland aloofness that has afflicted countless heroic leaders on screen, Dieudonné’s Napoléon knows how to deliver a joke when it is required of him. With the help of Gance’s exquisite visual stylisation, how could he not? In one of his earliest conversations with Joséphine (Gina Manès), Napoléon (and the audience) cannot help but be conscious of the black fan that Joséphine waves back and forth in the lower half of the frame. Joséphine asks the military man, “Which weapons are the most dangerous, monsieur?” Napoléon replies, “Fans, madame.”

Gance’s cast all have big shoes to fill, and often fill them with big performances. The boisterousness of the supporting characters, much in keeping with the acting style of the time, is infectious, but the real treat here is in the cast of villains. The so-called Three Gods of the revolution are introduced as a triptych, composed of perversion (Antonin Artaud as Jean-Paul Marat), zealotry (Alexandre Koubitzky as Georges Danton) and calculating inhumanity (Edmond van Daële as Maximilien Robespierre). This formidable trio is later joined by Abel Gance in the role of the Louis de Saint-Just, who Gance plays with great restraint as a cold-hearted dandy revolutionary – still craving blood, even as Robespierre’s conscience creeps up on him. Besides these four figureheads of the revolution, few of the villains get much in the way of dimensionality, which is hardly surprising in a film trading mostly in archetypal characters – some fascinating, some quite peculiar, but all performing in service of a story that aims to do justice to mythological figures, rather than social realism. But the talent that a film such as this attracts will inevitably yield memorable moments, even in fleeting roles. The wonderful Jean d’Yd stands out with his quiet comic performance as La Bussière, the self-appointed “eater of documents,” who saved the lives of countless victims of the Reign of Terror by consuming pages from the dossiers assembled against Saint-Just’s prisoners. In another display of understated grace, Percy Day as Admiral Hood sets a precedent for the universal trope of the dry English villain by calmly sipping tea from a China cup as he orders the French fleet to be set alight at Toulon.

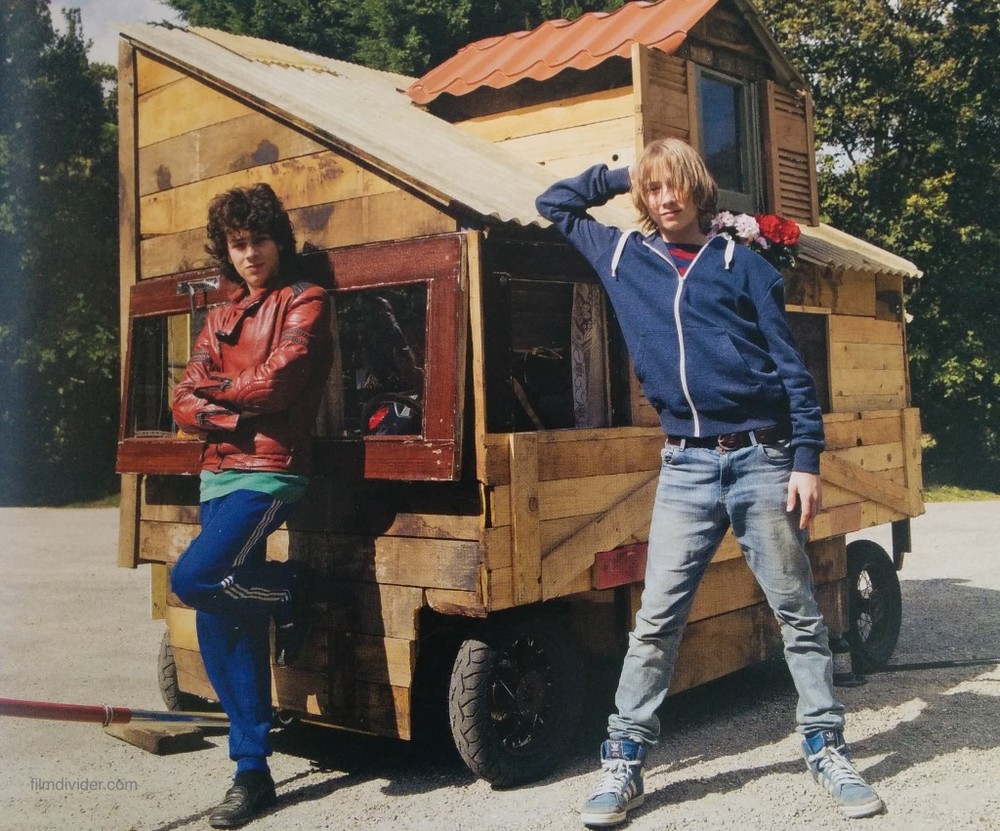

View fullsize

Vladimir Roudenko as the adolescent Napoléon.

View fullsize

Albert Dieudonné as the adult Napoléon.

Dieudonné’s on screen prowess and nobility represents the hagiographic nature of this depiction of the anti-tyrannical hero to whom Ludwig van Beethoven once wished to dedicate his third symphony. Sadly we can never know how Dieudonné’s rigorously researched portrayal of Napoléon would have changed in future instalments of Gance’s series, as Napoléon transformed from a hero of the people to a tyrant in his own right. A particularly poignant but also troubling scene arrises in the final act, in which Napoléon stops his carriage at the vacant National Assembly building, to contemplate the history of the revolution before he rides to invade Italy. Standing in the vast, empty room, Napoléon envisions a conversation with the ghosts of Saint-Just and the Three Gods of the revolution. He tells them of his dream of a Europe without borders, where any man can roam freely and say that he finds himself still in his fatherland. The speech inspired laughs, cheers and a rousing moment of spontaneous applause at the Royal Festival Hall from an audience, who found out earlier this year that their country will soon leave the European Union. Napoléon’s reverie for the spirit of the revolution and his vision of a liberated Europe is true to the character but emotionally confusing in this scene. Narrative conventions and the real-life atrocities committed in the name of the revolution necessarily cast Saint-Just and the Three Gods as villains, yet here Napoléon looks to them as sanctified figures. It is not wholly inappropriate, especially given Gance’s conscious emphasis through-out the film on the bloody hands that forged the greatness of the French Republic. Still, one cannot help but feel that these revolutionary figureheads were ultimately underserved by the filmmakers. This is to say nothing of the irony that is imposed upon this scene by the ignominious history that follows the early chapters in the life of Napoléon Bonaparte.

As a fan of heroic mythology and admirer of the techniques of cinematic storytelling I was constantly moved by Gance’s boundless invention. In many ways, Napoléon is a key text in the creation of modern cinema, and the action genre in particular. It begins in the heat of battle, where teen-aged military cadets range across a snow-covered landscape, engaged in a full-scale snowball fight. The young Napoléon (Vladimir Roudenko) commands a paltry ten boy soldiers against forty aggressors, while the monks and schoolmasters of the military academy look on with great interest. Even from this early age, Napoléon does not let overwhelming odds snatch victory away from him. Rather than cower behind the walls of his snow fort, Napoléon commands his tiny army to rush at the enemy. Mere minutes into the film, Gance is already challenging and broadening the conventions of cinematic technique with handheld camerawork and iconoclastic imagery of Napoléon’s tenacious id, driving him towards victory. Gance’s use of cross-faded images, rapid cutting and point-of-view shots throws the audience into the chaos and visceral thrill of something as laughable as boys playing at war in the snow. As the sequence sets up the boy, who will become France’s greatest hero, it also throws open the doors to the sequences of battles and marching armies yet to come, as well as revolutionising the practice of montage in cinema. Gance does not rest for long. As the proud but isolated Corsican cadet fights against the bullies tormenting him, Gance again takes the delightful chaos of a childish brawl as a spring board for further technical experimentation and splits the screen nine ways during a pillow fight in the boys’ dormitory. Seeing such an audacious and original assault on the visual language of cinema, all in service of an emotional narrative of mythological proportions, moved me to tears. I can only liken the thrill, dynamism and visceral impact of the sequence to that of a Jackson Pollock painting. To witness it in a vast auditorium with the rousing fanfare of Davis’ score beneath the flickering screen absorbs the viewer in the same way as seeing a Pollock painting in a gallery. Often it is silent cinema, more so than any other, that demands to be seen in a “live” performance.

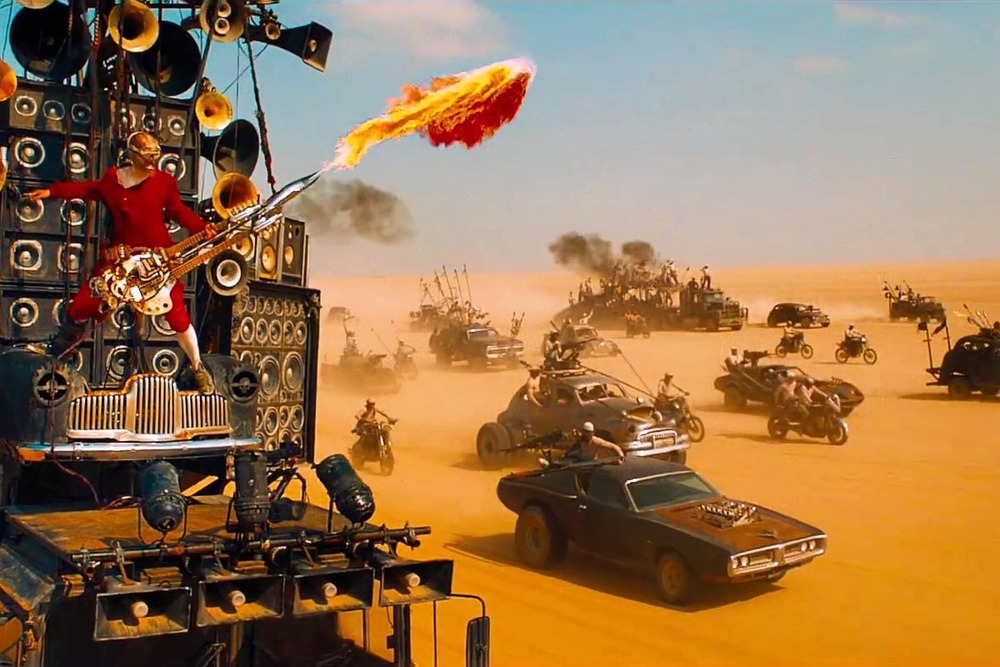

View fullsize

POLYVISION: Abel Gance’s three-camera, three-screen method for vastly expanding the scope of Napoléon’s final act.

Sadly the film’s latter half cannot live up to the impact of the first two acts. The third act sags terribly as a love-stricken Napoléon courts Joséphine in a drawn-out romantic comedy. The tonal shift here does not undermine the film’s cohesion but kills the film’s pace. In a similar way, Napoléon’s arrival at the French camp in Italy retreads the thrust of Naopléon’s arrival in Toulon: the army is poorly supplied, undisciplined and commanded by arrogant generals, who Napoléon must bend to submission through the strength of his personality alone. But it is reasonable to suspect that Gance was aware of this and so took the opportunity to vastly expand the scope of Napoléon’s triumph as a leader by adding two more screens! By using three cameras and three projection screens to create a super-wide triptych of images, Gance created what he called “Polyvision”, an early forerunner to Hollywood’s Cinerama system. Watching the vast expanse of the army rise as one to stand to attention for Napoléon amplifies the emotion of the sequence in a way that is unique to the vast canvas of cinema. Scenes such as these are rarely used tools in today’s blockbusters, belonging to an older age of dramatic staging. Witnessing the effect of thousands of extras performing a single gesture en masse makes the crumbling skyscrapers and explosive space battles of today’s big-budget entertainment seem hollow and dispensable by comparison. In this final act, as Napoléon stokes the fires of his army with the spirit of patriotism for France and a united Europe, Gance uses his Polyvision to layer cross-faded images of lands conquered and lands soon to be conquered over vast images of Napoléon’s army marching towards victory. The final coup de théâtre, using the Polyvision technique, is the creation of the tricolour through different colour tinting in each of the three frames. The resulting emotions are a testament to the power of cinema to stir up patriotism for the revolution, even in the hearts of France’s oldest enemies: the tea-sipping English! But all of this imagery would lack for lasting impact without music to accompany it, especially the unbeatable patriotic anthem of ‘La Marseillaise’, which Gance features prominently in the film and Carl Davis uses to maximum effect in his meticulously researched score.

The importance of Davis’ score to this restoration must not be underestimated – without it, the experience loses its authenticity and the film loses its spirit. Like the composers and conductors of the silent film era, Davis draws upon the beloved classics of composers like Mozart, Beethoven and Haydn to create a montage of his own, which reaches back in time to the romantic history of 18th Century Europe. Davis also ensures that the score possess a heritage of French folks songs and classical compositions. But Napoléon‘s reliance on particular folks songs, marching songs, Corsican melodies and anthems of the period is pronounced in a way that is reflected on screen. The filmmakers have left composers-cum-cinema-historians various cues, which are easily interpreted by using Wagner’s principals of thematic musical narrative – principals which govern the composition of our best modern orchestral film scores. The inspiring spirit of the revolution is present and correct on screen whenever variations on ‘La Marseillaise’ can be heard. When the eagle of destiny is present at the climax of key moments in Napoléon’s ascent to greatness, the grandiosity of Beethoven can be heard. Throughout, Davis draws heavily from Beethoven’s third symphony, ‘Eroica’, which Beethoven initially wished to dedicate to Napoléon as a hero of the people in Europe – that is until Napoléon crowned himself Emperor of France in 1804. Davis is an seasoned composer and conductor of silent film scores, and a diligent scholar of the conventions of silent scoring in the early 20th Century. As one can imagine, comedy and action are among the toughest genres for which an orchestra can perform, and Davis and the Philharmonia deliver deft comic timing by pre-empting Abel Gance’s jokes, rather than reacting to them. The diametric opposites of the French Revolutionaries, the British, are ripe targets for mockery throughout the film, and the audience is primed for a good laugh by the orchestra’s introduction of pompous variations on ‘God Save the Queen’ and ‘Rule Britannia.’

But ‘La Marseillaise’ is the anthem around which the characters on screen and their audience must rally. It is key to inspiring patriotism for the ideal that the French Revolution represented, to which Napoléon once dedicated himself. Davis’ composition of the complex and rousing collage of anthems for the spectacular final montage sells us the dream in a way that is effortlessly emotional and un-esoteric, as all good anthems are wont to be. I suspect that this musical power is what Abel Gance was reaching for with his three-screen triptych, cross-faded montage and massive imagery. In this respect, Gance’s efforts were successful but, unlike Carl Th. Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, he could not have marched towards the future of cinematic storytelling without the might of Europe’s musical history behind him.

Napoléon comes out in limited cinematic release in the UK and on DVD, Blu-Ray and BFI Player on 11th November 2016.

View fullsize

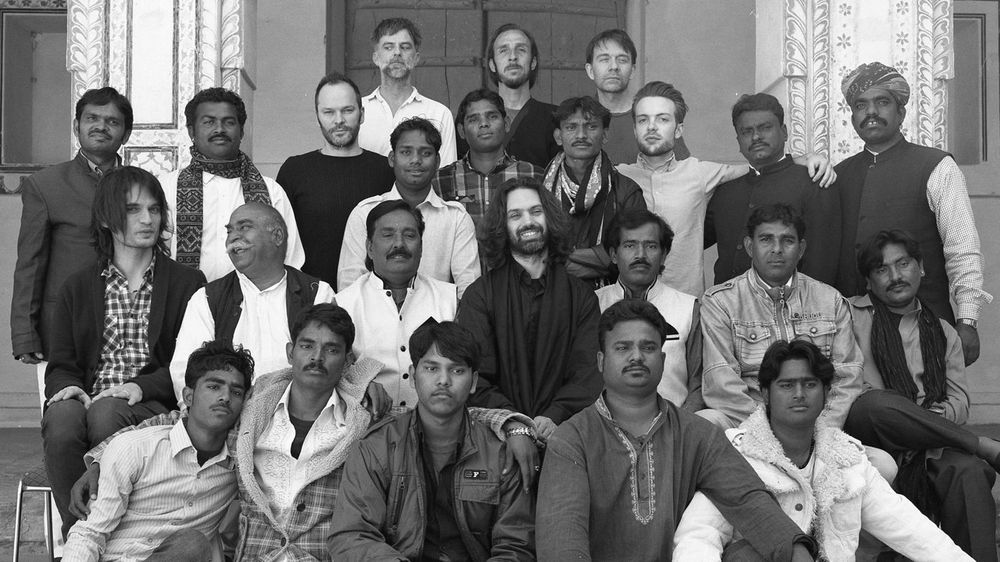

Carl Davis and the Philharmonia Orchestra celebrate the stars and director of Napoléon at the Royal Festival Hall on 6th November 2016.